Wilton: Town of Mints, Saints and Carpets

by Moira Allen

The town of

Wilton lies just ten minutes away from downtown Salisbury (or

half an hour if you happen to hit "rush-hour" traffic).

It's a lovely town that offer several sites worth seeing, and

it's well worth a visit if you'd like to shop or get a bite to

eat in relative peace and quiet. The town of

Wilton lies just ten minutes away from downtown Salisbury (or

half an hour if you happen to hit "rush-hour" traffic).

It's a lovely town that offer several sites worth seeing, and

it's well worth a visit if you'd like to shop or get a bite to

eat in relative peace and quiet.

The town takes its name from the same source as the county of

Wiltshire as a whole: The Wilsaetes tribe, who took their

name from the River Wylye, near which they lived. Wilton is

first mentioned in 802 as Wilsaete, and later as Wiltunscir

(Wilton-shire), but probably existed as a town or village since

at least the middle of the 8th century. By the 9th century, it

had become the royal seat of the kingdom of Wessex, and remained

so until King Alfred moved the royal seat to Winchester. It was

also, on and off, the seat of the bishop of Wiltshire; in 970,

Oswulf, described both as the bishop of Sonning and the bishop of

Wiltshire, was buried at Wilton.

Several factors contributed to Wilton's importance during the

Middle Ages. It was the site of the oldest mint in Wiltshire;

coins were first minted in Wilton during the reign of King Edgar

of Wessex (great-grandson of Alfred the Great), who came to the

throne in 959. The mint remained active until Henry III shut

down all "provincial" mints in 1250, despite a brief

retreat to the safety of Old Sarum when Swein's Danish Vikings

sacked Wilton in 1003. Since a law of Athelstan prohibited the

minting of coins except in a "port" (town), this

indicates that Wilton had a town charter for an early date.

Wilton was also the site an abbey dedicated to St. Mary and St.

Bartholomew. This was originally founded as an Anglo-Saxon

nunnery by Weolkstan, Earl of Ellandum, in 773, and from the

beginning it attracted nuns from noble and even royal families;

it was also the home of Wilton's own saint, Edith, who was the

daughter of King Edgar. Her tomb attracted many visitors and

pilgrims to Wilton, for she had a reputation for healing. In the

13th century the nunnery was replaced by a Benedictine abbey. By

the time it was closed by King Henry VIII in 1539, its income was

the fourth highest in the country. Wilton was also believed to

have possessed no fewer than twelve separate churches at its

heyday.

Finally, Wilton was located at the convergence of several major

roads, including the "Port Herepath" (town highway),

the "Wiltenweye" leading from Hampshire, and the

"Theod Herepath" (people's highway) that lead to the

Avon Valley. Traffic on these roads made Wilton the ideal

location for a market town. Its town charter was confirmed in

1154 by King Henry, and again by King John in 1204. This latter

charter cost the burgesses 100 marks and 700 ells (875 yards) of

linen, suggesting that clothmaking was by this time one of the

town's primary trades.

Wilton was also an excellent defensive location, being set upon a

ridge and enclosed by rivers on two sides. Despite this, it was

burned to the ground twice by the Danes. In 871, the Danes

defeated King Alfred's forces at Wilton, leading to a temporary

truce between the Wessex Saxons, who offered to pay a Danegeld to

buy time to regroup. In 1003, the town was burned by the Viking

forces of Swein, who had attacked England in retaliation for King

Ethelred's massacre of Danes residing in England (including

Swein's sister). Ultimately Swein defeated Ethelred and drove

him into exile, becoming the de facto king of England.

The town was put to the torch yet again in 1143 by the forces of

Empress Maud, led by Robert of Gloucester, who surprised King

Stephen's army in the process of attempting to fortify the town

(and more specifically, the abbey). Being built mostly of wood,

the abbey was nearly completely restored, but was soon rebuilt in

stone. Yet another fire destroyed 25 houses, workshops, looms

and outbuildings in the weaving district in1769, but at least

this had nothing to do with invading armies!

The ultimate blow to Wilton's prominence, however, was not due to

marauding Danes, but to the rise of Salisbury in the 13th

century. With its new cathedral, Salisbury became the official

bishop's seat for Wiltshire, and the growing town began to

supplant Wilton's own market. A new bridge over the River Avon

added to Wilton's problems, for it created a bypass that directed

traffic to Salisbury. As towns were repopulated after the Black

Death, residents and tradespeople tended to move to Salisbury,

leaving houses and shops in Wilton to literally stand empty and

decay. Eventually, Wilton's primary economic activity was the

cloth trade, augmented by the wool market that had once belonged

to the abbey, but was granted to the town in 1433. By 1901,

nearly 100,000 sheep were being sold annually in this market.

In 1741, the Earl of Pembroke smuggled two French weavers into

England to introduce new carpet-weaving techniques to Wilton.

This resulted in a new rise in prosperity as carpet factories

sprouted up around the town. However, both cloth and carpet

factories suffered another blow in the 19th century when many

proved unable to make the switch from water to steam power. The

main carpet factory in Wilton shut down in 1904, but was reopened

by Lord Pembroke as the Wilton Royal Carpet Factory, which

flourished until being shut down again in 1995 by another

takeover. It again reopened and today produces high-quality

Wilton and Axminster carpets (and if you take the Wilton Carpet

Factory tour, you'll learn how to tell the difference!).

Today, about all that remains of medieval Wilton is the layout of

the streets (and even some of the names have changed). From the

17th century onward, waves of new building and reconstruction

have either obliterated or refaced the town's medieval buildings.

Most of the twelve churches of Wilton had vanished by the 18th

century, and many had been in ruins long before that. In 1738, a

new town hall was built over the old Guildhall, and in 1845,

Wilton's new "Italianate" church replaced its last

medieval parish church (whose ruins can still be seen in the town

centre, as part of a "Garden of Peace" established in

1938).

When Henry VIII dissolved Wilton Abbey in 1539 (or 1536,

depending on which accounts you read), most of the estate was

granted to Sir William Herbert, who became the first Earl of

Pembroke in 1551. He built the first Wilton House on the site of

the abbey, using much of the abbey's stone in the process.

Indeed, many houses in Wilton are believed to include stones from

the old abbey and chapels, including flints gathered by St. Edith

herself.

Today, Wilton offers three major attractions that should not be

missed: Wilton House, the Italianate Church, and the Wilton

Carpet Factory Museum.

The Wilton Italianate Church

Wilton's Church of St. Mary and St. Nicholas, also known as the

Italianate Church, was built between 1841 and 1845 to replace the

original medieval parish church that was falling into decay. The

new church was designed by Thomas Henry Wyatt and David Brandon.

The first thing that will strike the visitor

about this impressive church is that it does not look like one's

typical English parish church. The Byzantine design is inspired

by a Roman basilica, while the mosaics of the nave will put one

in mind of Greek or Russian Orthodox styles. This may not be a

coincidence, as the church was built at the behest of the Dowager

Countess of Pembroke, who was born in Russia. Some believe that

the church's unusual north-south orientation (most English

churches are built upon an east-west axis) was also the wish of

the countess, as this was a custom in Russia. It's likely,

however, that this orientation was chosen so that the church

would directly face the road. The first thing that will strike the visitor

about this impressive church is that it does not look like one's

typical English parish church. The Byzantine design is inspired

by a Roman basilica, while the mosaics of the nave will put one

in mind of Greek or Russian Orthodox styles. This may not be a

coincidence, as the church was built at the behest of the Dowager

Countess of Pembroke, who was born in Russia. Some believe that

the church's unusual north-south orientation (most English

churches are built upon an east-west axis) was also the wish of

the countess, as this was a custom in Russia. It's likely,

however, that this orientation was chosen so that the church

would directly face the road.

Many of the construction materials were imported from Europe,

including black marble columns from the 13th-century Capocci

Shrine from the Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (which had

subsequently ended up in the garden of Horace Walpole).

Materials from this shrine are also included in the pulpit, which

is particularly striking with its twisted columns and colored

stone panels (known as Cosmato work). The pulpit was created by

Peter Cavalini, who designed the tomb of Edward the Confessor at

Westminster Abbey. The marble columns supporting the arches at

the south end of the side aisles date from 200 BC, and come from

the Temple of Venus at Porto Venere on the Gulf of Spezia. The

lions supporting the front doorposts are carved from stone

brought from the Isle of Man.

The windows include several 12th- and 13th-century panels from

France, as well as painted Flemish or German roundels from the

16th-century. The rose window includes glass from the 16th

century that was originally looted by Napoleon's army. The

church also includes windows brought from the original parish

church, as well as a number of fine contemporary Victorian

windows. A number of memorials and tombs were brought

from the original church, while newer memorials include the

recumbent alabaster figures of Lord Herbert of Lea (d. 1861) and

his mother Catherine, the Countess of Pembroke (d. 1856). The

Dowager Countess left £1,000 in trust for the church, which

was to be invested to maintain the stained glass, mosaics, and

other ornamentation.

The church stands upon the site of an older St. Nicholas church,

which was already in ruins by the 1400's. Bones disturbed by the

building work are housed in a stone sarcophagus, which stands

against the outer southern wall. Another dramatic feature is the

church's 105-foot campanile, which originally contained six bells

recast from the bells of the original parish church. A new set

of bells was installed in 2000 for the Millenium, and the

originals were sent to Australia.

Wilton House

Wilton House stands on the site of Wilton Abbey, which was

founded as an Anglo-Saxon nunnery in 773 and became a Benedictine

abbey in the 13th century. When it was surrendered in 1536 or

1536 to King Henry VIII, he granted the abbey and lands to Sir

William Herbert, creating the first Earl of Pembroke. Herbert

began building a Tudor manor on the spot in 1543.

Since then, the house has undergone an almost continuous process

of building, expansion, and rebuilding. In 1644, the house was

garrisoned briefly by the Royalists during the Civil War, when

the king sent some of his cannons to the house with a company of

foot soldiers to guard them. The Earl of Pembroke, however,

seems to have come down more on the side of Parliament, as he did

not lose any of his estates during the Interregnum; the house has

remained in the same family since the Earldom was

established.

In 1647, the house was nearly completely destroyed by fire, but

was subsequently rebuilt to a design by Inigo Jones. The 9th

Earl of Pembroke (1733-1750) was known as the "Architect

Earl," and was responsible for landscaping the grounds and

gardens as they are seen today. This included diverting the

River Nadder so that it flowed past the house, to be spanned by a

magnificent Palladian bridge. Across the bridge, below the brow

of the hill, one can see a small classical temple. The 10th Earl,

a cavalry officer, built the Riding School at the northwest

corner of the house, which includes kitchens, a laundry, and

other quarters.

This is where the visitor enters Wilton House today. The main

room of the Riding School is now a miniature museum, filled with

items that have been found in the area or that are associated

with the house. Among these are several highly carved Roman

coffins and other Roman stones. A somewhat more unusual exhibit

is the set of leather horseshoe-covers that were used to shield

the hooves of the draft horses used to mow the extensive lawns

surrounding the house, back when a "riding mower" meant

something very different indeed! You'll then be ushered into a

small room to watch a short and quite entertaining film about the

history of Wilton House, narrated by the ghost of one of the last

abbesses. From there, you proceed through a reconstruction of a

16th-century kitchen (with ghost), forward in time to a Victorian

laundry, and finally into the main house itself.

Wilton House is known for its vast art collection, much of which

was acquired by the 8th Earl. Some rooms are dominated by a few

large paintings; others are lined wall-to-wall and

floor-to-ceiling. Don't miss some of the more interesting pieces

besides the artwork, however, such as a beautiful, multi-colored

glass chandelier, and matching cabinets of inlaid stonework. And

remember that while much of the house is on display, Wilton House

is still the residence of the Earl and Countess of

Pembroke; in fact, during our visit, we glimpsed the countess

taking her dogs for a run by the river.

The gardens are well worth a look, and when you've finished

with the grounds, Wilton House offers a very nice tea-shop where

you can end the afternoon with a cream tea and a choice of cakes

or sandwiches. It was my husband's first introduction to the

cream tea, which he fortunately handled better than my own

"first time," when I assumed that the clotted cream

went into your tea rather than onto the scone.

The Wilton Carpet Factory

The Wilton Carpet Factory is located the Wilton Shopping Village

just across the road from Wilton House, so it is easy to combine

a visit to both sites at once. A carpet factory might not seem

like the most interesting place to visit (our thought was

"well, we're here..."), but it is more intriguing than

it sounds. A series of wall panels and photos gives the visitor

an overview of the history of carpet-making in the area; then,

you're given a tour of the modern factory and a short lesson on

how Wilton and Axminster carpets are made today. The tour

includes a history of the evolution of many of the machines used

in the process; some of the older ones still use a punched

pattern roll much like a music roll in a player piano. The tour

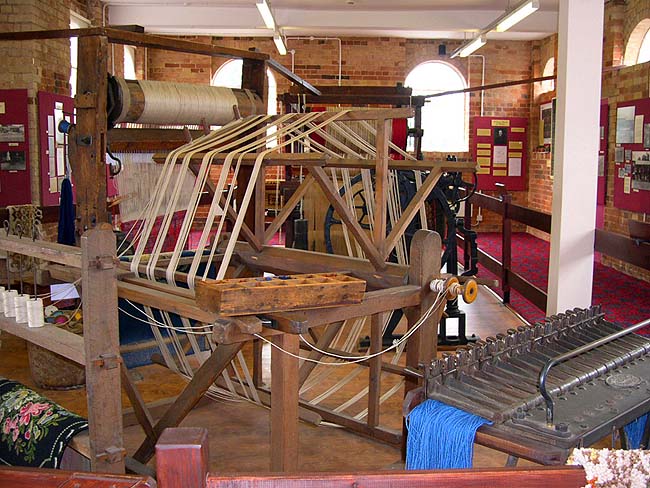

concludes in a small museum housing a variety of historic looms

and other weaving and carding devices, as well as a small

collection of trade artifacts from the town of Wilton.

From there, you might wish to visit the sandwich shop for a quick

lunch, and do a spot of shopping. The "shopping

village" consists of old factory buildings, many of which

now house factory outlet stores. But beware: if, on your way into

or out of the shopping village, you look remotely as if you might

be carrying food, be prepared to be mobbed by the Wilton Duck

Gang. Many locals obviously come prepared for this, and can be

found buried to the ankles in greedy ducks of just about every

shape, size and color, from itty-bitty ducklings to exceedingly

fat adults. Swans glide a bit more sedately on the River Nadder,

which flows beneath the bridge leading to the carpet factory and

once provided the power for its machines.

Wilton Italianate Church

Wilton Carpet Factory Museum

Wilton House

The Wilton Duck Gang

Related Articles:

- St. Edith of Wilton, by Moira Allen

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/history/edith.shtml

- Salisbury: Designed to In-Spire, by Moira Allen

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/salisbury.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article and photos © 2007 Moira Allen

|