The Roman Baths of Bath

by Moira Allen

When one stands before the mysterious green waters of the great pool at Bath, overlooked by time-darkened statues of Roman emperors, one cannot help but feel transported in time, back to the days when Roman citizens and centurions bathed in this pool and offered homage to the patron goddess of the waters, Minerva.

When one stands before the mysterious green waters of the great pool at Bath, overlooked by time-darkened statues of Roman emperors, one cannot help but feel transported in time, back to the days when Roman citizens and centurions bathed in this pool and offered homage to the patron goddess of the waters, Minerva.

It's an illusion, of course. The familiar green hue of the pool is not the result of mystery, but of algae, caused by the water's exposure to the open air. In Roman times, the pool was roofed over, its waters -- well, perhaps not crystal clear, but certainly clear. The "Roman" statues that gaze down upon the pool from the upper walkway are Victorian. In fact, the Roman portion of the building now surrounding the Great Bath extends only about six feet above ground level; the outer wall, parapet and statues are less than 200 years old.

But that does not diminish the mystique of the Baths -- a mystique that is as attractive to tourists today as it was to the Romans, the Georgians, and the Victorians who flocked to their new-found "spa." And there is much to see, even if one can no longer take a dip in the murky pool (though one can still sample the mineral water of the original spring in the famous "Pump Room").

I had visited Bath in 1979, so when I returned nearly a quarter of a century later, I assumed I had "seen" the baths. I was mistaken! In 1983, vast new sections of the complex were opened up to public view, revealing the results of ongoing excavation into a structure that was both a place to bathe and the "Temple of Sulis Minerva." One can now view several sections of the bathing complex, including the calidarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath), and frigidarium (cold bath). Most Roman bath houses were not nearly so large, due to the difficulty of heating so much water -- but at Bath, the water comes preheated, so to speak, gushing from the Sacred Spring at a temperature of 46° C (114.8°F). While the west baths (a series of warm and hot pools) include sections of beautifully preserved pilae -- the stacked tile supports of a hypocaust system -- this system was used to heat the floors and walls, not the waters.

Of Pigs and Princes

The history of the baths does not begin with the Roman occupation of Britain, however. According to legend, the original town of bath was founded by Bladud, purported to be the eldest son of the Celtic king Lud and father of King Lear. As a young man, Bladud supposedly contracted leprosy, and chose to leave his home to become a swineherd far from home (the towns of Swineford and Swainswick are both given as possible locations). His pigs weren't doing too well in the health department either, as they apparently had scurvy. One day, however, Bladud observed one (or several) of his pigs wallowing in a patch of hot black mud. (More dramatic versions of the legend have Bladud leaping into the mire to rescue a pig that was in danger of being sucked to its doom.) Bladud observed that the wallowing pig (or pigs) emerged clean of scurvy, so he tried bathing in the mud himself, and his leprosy was cured. He returned to court, eventually became king himself, and founded both the town of Bath itself and a temple to the Celtic goddess Sul at the site of the spring.

In reality, the town of bath may not have been built until at least 1000 years after Bladud, but evidence indicates that it was important to the Celts. Five hillforts have been found on the surrounding hilltops, including the forts at Lansdown and Solsbury Hill. The only physical evidence discovered thus far of pre-Roman worship at the spring, however, is the remnant of an earthen bank projecting into the spring.

The Roman bath-and-temple complex evolved over time. The earliest Roman structure was an irregular lead-lined stone chamber that surrounded the spring itself. The resulting open pool was later roofed over, while statues and columns apparently arose from within the spring itself. This roof ultimately collapsed into the water, possibly in the 6th or 7th century, but the oak piles that were sunk into the mud when the enclosure was first built continue to support the reservoir walls to this day.

The temple to Sulis Minerva was erected in the 1st century AD, and was modified in the 2nd century. It remained in use until late in the 4th century, but eventually collapsed from disuse as Christianity supplanted the gods of Rome. The temple would have housed the statue of Minerva (whose head can now be seen in the tour of the Roman excavations of the baths). The tour of the baths now takes one beneath the Pump Room to the foundations of the temple, where one can see portions of the excavations, altar stones, and bits of mosaic flooring. A wooden model shows how the complex would have looked at its heyday, while a video demonstrates the successive stages of construction.

Of Curses and Gorgons

Among the artifacts that have been dredged from the foundations and the waters of the baths are an abundance of "curses". These were written on thin strips of lead, rolled up, and cast into the sacred pool. Often they were written backwards, as this was believed to give them additional magic power. They were written on lead because it was believed that if the curse floated, it would rebound upon the writer of the curse rather than its intended victim.

The text of several of these curses is on display in the corridor overlooking the sacred spring. Many ask the goddess to visit vengeance of the most violent sort upon miscreants who have committed the most petty of crimes. One, for example, proclaims "To Minerva the goddess of Sulis I have given the thief who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether slave or free, whether man or woman. He is not to buy back this gift unless with his own blood." (It is difficult to avoid contrasting this with the Biblical injunction that "If someone steals your coat offer them your cloak as well...")

One of the most well-known discoveries relating to the temple, however, is the great round stone face that is part of the temple frieze. This was discovered when workman began to dig the foundations of the Pump Room in 1790. This face -- wreathed with waving locks of hair and adorned with an unmistakable mustache -- has been reproduced on just about all things Bath: book covers, pamphlets, mugs, jewelry. When I saw it on the cover of a guide book in the gift shop in 1979, I asked the attendant what it represented -- and was confidently informed, "It's the Gorgon Head."

One of the most well-known discoveries relating to the temple, however, is the great round stone face that is part of the temple frieze. This was discovered when workman began to dig the foundations of the Pump Room in 1790. This face -- wreathed with waving locks of hair and adorned with an unmistakable mustache -- has been reproduced on just about all things Bath: book covers, pamphlets, mugs, jewelry. When I saw it on the cover of a guide book in the gift shop in 1979, I asked the attendant what it represented -- and was confidently informed, "It's the Gorgon Head."

Having recently graduated with a degree in anthropology and folklore, my instant reaction was "No way!" "Way," I was assured (well, perhaps not in those precise words). According to the attendant, experts had confirmed that this was, indeed, a representation of a gorgon -- and that, apparently, it was "common" for gorgons to be portrayed as (a) male and (b) sans obvious snakes.

Today, one has only to search on the term "gorgon" to discover that there are, indeed, countless Greek and Roman representations of Medusa and her sisters. Some represent the gorgons as beautiful ladies having a bad hair day; others represent them as hideously ugly; all, however, clearly represent them as female. In many, the gorgon is sticking out her tongue; in some, she has fangs. But a mustache?

The gorgon interpretation is apparently based on the fact that there are, indeed, snakes entwined in the figure's hair -- though most other images of gorgons show no hair at all, only snakes. This identification is now coming into question. According to the Bath website, another possible interpretation is that the face is that of Oceanus, as it bears a strong resemblance to an image of Oceanus on the great silver "Neptune" platter from the Mildenhall hoard. The mustachioed face on the Mildenhall platter is surrounded by figures of sea-nymphs, tritons, and dolphins; tritons and dolphins also appear on the Bath frieze. (Devotees of Celtic lore claim that the face is actually a Celtic sun god; however, it seems unlikely that Roman architects would have carved the face of a Celtic god upon the frieze of a temple to Minerva, even if the sculptor was, in fact, a Gaul, as is now believed.)

Down the Drain -- and Back Again

After the Romans pulled out of Britain, the baths fell into decay. Over the next few centuries, rooves fell in, walls collapsed, mosaics and sculptures were covered up, and the site was finally forgotten. The area was still known for its healing waters, however, and by the late 18th century, it was beginning to experience a rebirth as a fashionable resort. It was a visit from Queen Anne in 1802, however, that helped transform Bath from a sleepy backwater (no pun intended) into one of the most popular hot-spots of Georgian society.

After the Romans pulled out of Britain, the baths fell into decay. Over the next few centuries, rooves fell in, walls collapsed, mosaics and sculptures were covered up, and the site was finally forgotten. The area was still known for its healing waters, however, and by the late 18th century, it was beginning to experience a rebirth as a fashionable resort. It was a visit from Queen Anne in 1802, however, that helped transform Bath from a sleepy backwater (no pun intended) into one of the most popular hot-spots of Georgian society.

Richard "Beau" Nash was the leading architect of this transformation. Nash was responsible for the building of Bath's Assembly Rooms (which now house the Costume Museum), and he also established a variety of rules to govern polite behavior. Bath began to rival London as the place to spend "the season." Much of the architecture surrounding the baths today dates from this period of Georgian revival.

It was not until 1880, however, that sewer workers uncovered the first glimpse of the Roman structures that underlay the Georgian spa. According to one of the guides, the workers had actually been called in to deal with a "leak" that kept erupting in someone's basement. This led to the discovery of the baths and their treasures. The walls, columns and parapet that surround the Great Bath were built in the Victorian period -- along with the statues that gaze down impassively upon the green waters and the throngs of tourists.

Victorian, yes... But as you gaze upon the green pool, or feel the steamy heat of the water pouring from the Roman outlet on its way to the River Avon, it's very easy to forget that you are in a modern museum, and to let your mind slip back to a more ancient time. And perhaps that's not an illusion after all.

|

|

|

|

| Victorian sculptures of Roman emperors stand guard over the baths from the upper terrace. |

|

|

|

| Two stones from the altar to Minerva, and an inscribed temple stone. |

|

|

| Stacked tile pilae from the West Baths hyppocaust system, used to warm the floor and walls. |

|

|

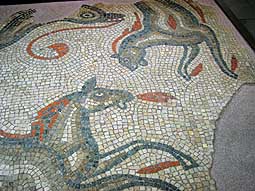

| Temple Mosaic |

|

|

| Original temple floor; frigidarium (cold pool) |

|

|

| The Great Bath (and some modern bathers) |

|

| Rotunda ceiling of the main entrance to the Baths. |

Related Articles

- The Beauty of Bath, by Michele Deppe

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/bath.shtml

- Bath Timeline, by Darcy Lewis

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/towns/bathtime.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article and photos © 2005 Moira Allen

|