Four Great Abbeys and Priories of Yorkshire

by Dawn Copeman

Before they were dissolved by King Henry VIII, the abbeys and

priories of Yorkshire were some of the most imposing buildings in

the land. When you visit them today, they are beautiful,

peaceful, atmospheric ruins, either colorfully overgrown with

wild flowers or a mass of carefully planted, traditional gardens.

They are used as the settings for outdoor performances of plays,

concerts, and proms. But there are thirteen ecclesiastical ruins

in Yorkshire, so what makes these four so special?

Well, one of them was instrumental in the development of a food

industry that is still in business today. One spearheaded the

establishment of nineteen monasteries in just over 100 years and

demonstrates the animosity between the various orders of monks.

One is a rare example of an unusual monastic order, and one of

them played an important part in the preparations for D-Day, a

role so clandestine that has only recently been revealed.

Oh, and just for the record the largest monasteries were called

abbeys, as they were ruled by an abbot or abbess. The smaller,

daughter houses of these abbeys were usually, but not always,

known as priories.

Kirkham Priory

Kirkham Priory was founded on the banks of the River Derwent by

Walter L'Espec in 1120. Walter L'Espec was also the original

owner of nearby Helmsley Castle and later went on to donate the

land for Rievaulx Abbey. Legend has it that he founded Kirkham

Priory for the Augustinian canons at the place where his only son

had died after falling from his horse.

Unfortunately, we do not know from which abbey the canons

came, but we do know that the Augustinians lived a life of

service to the local community and took over the running of the

parish churches. We also know that when Rievaulx was built some

twelve years later the canons had to fight for their survival, as

it was suggested that they move elsewhere and let the Cistercians

take over Kirkham. They managed to come to an agreement with the

Cistercians that permitted them to stay, but we don't know what

the terms were.

We know that the priory flourished, however, because you enter

Kirkham Priory through an elaborately carved gatehouse that dates

from the 13th century. The gatehouse is decorated with

sculptures of George and the Dragon, David and Goliath and

heraldic shields, amongst them the arms of Espec and de Roos --

de Roos being the family who built most of Helmsley Castle

following the death of Espec.

Inside the priory we can see the remains of a vaulted cloister,

the lavatorium and the church. The rest of the priory is in

rubble, but it still gives us an impression of the layout and

size of the priory. The priory was used until its dissolution in

December 1539, but the buildings were often knocked down and

re-used as the needs of the priory changed. An example of this is

the 12th-century doorway that was later used as the entrance to

the 13th-century refectory.

The church was originally a small, cruciform, stone building,

which was rebuilt in 1180 and then gradually extended. There

were towers to the west of the church, and we can see the remains

of the southwest tower, complete with steps to the nave, near the

vaulted cloister. Excavations have shown that towers were planned

for the eastern end too, but these were never completed.

The most impressive structure here, however, is in the cloister:

the lavatorium. Built in the 13th century, the lavatorium is

where the monks washed before meals, and it is in remarkable

condition. Its carved, arched bays give us the best impression

of the splendour of this priory and you can even follow the

drainage pipes around the monastery to the river.

We do not know much of the history of Kirkham, or what happened

to Kirkham after the dissolution of the monasteries until 1944,

when it played a covert but vital role in the preparation for

D-Day.

Nestled as it is between a tree-lined hill and the Derwent,

Kirkham Priory was the perfect, secluded place for the British

army to test its landing craft. Soldiers climbed the priory's

ruined walls to gain practice in using the clambering nets they

would need to use in the destroyed towns and villages of France,

while the Derwent itself was used to test the waterproofing

compounds for tanks and other vehicles. The 11th Armoured

Division was just one of the many units stationed there. Kirkham

was so important that it was visited by both King George VI and

William Churchill. Visitors today can see a new exhibition on

Kirkham Priory's role in the war as well as the results of recent

excavations of the site including artistic impressions of the

infirmary.

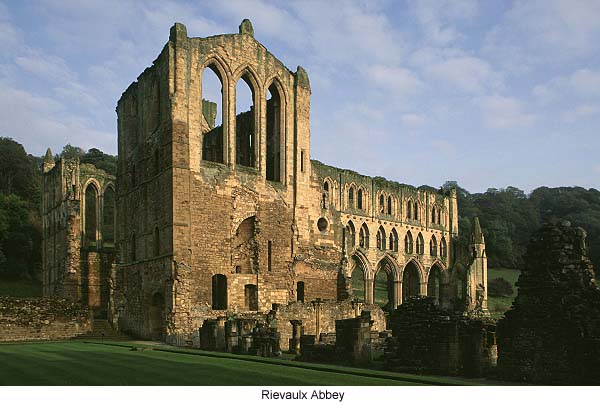

Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx Abbey was founded by St. Bernard of Clairvaux in 1132 on

land donated by Walter L'Espec. Rievaulx was the first abbey for

the Cistercian monks in the north of England and was used as

their headquarters for the colonisation of England. The

Cistercians, known as the White Monks because their habits were

made of undyed wool, believed themselves to practise a purer form

of the rules of St. Benedict than the existing Benedictine, or

Black Monks. In fact, even before arriving at Rievaulx, the

first twelve monks who were to set up the monastery caused an

upset whilst visiting the Benedictine abbey of St Mary's in York

when they inspired a group of monks to challenge the leadership

of their monastery. These rebellious monks later founded the

Cistercian Fountains Abbey.

The Cistercians had simple clothing, simple, unadorned

churches and a simple diet. They believed in doing lots of manual

labour, and each abbey was self-sufficient. Unlike the

Benedictines they rejected income from the church or manorial

rent; instead, they farmed lands through their 'lay brothers.'

At Rievaulx, they farmed sheep and sold wool. Rievaulx also

produced three saints -- William, its first abbot; Aelred, its

third; and a monk called Waldef. The shrine to Aelred can be seen

behind the high alter in the presbytery, and was a popular

pilgrimage destination for awhile. The shrine to William is in a

window in the chapter house.

In addition to upsetting the Augustinian monks at Kirkham Priory,

the Cistercians at Rievaulx also caused an upset with another

neighbour: the Cistercian Byland Abbey, over land ownership.

This led to the River Rye being diverted to form the boundary

between the two abbeys. Evidence of this engineering work is

still visible today in ditches and channels near the river.

At its peak, Rievaulx housed 150 monks and 500 lay brethren, but

the plague killed many and by the time of its dissolution in

1538, there were only 23 monks living here. The new owner of

Rievaulx, Thomas Manners, the Earl of Rutland, destroyed almost

all the buildings, but luckily for us he left the presbytery or

abbey church, the refectory and parts of the chapter house. The

presbytery is most impressiv, standing almost to its full height,

and so we can walk around its columns, gaze up at its arched

windows and gain an impression of the height of the building.

Rievaulx has recently been the subject of a new archaeological

study and we now know that the monks ate wild strawberries, that

the drains go deep underground, that the monks had an iron

foundry and that they used stained glass in their church. These

recent findings are explained in a new exhibition.

Jervaulx Abbey

Jervaulx, another Cistercian Abbey and a daughter abbey of

Rievaulx, was founded by John de Kinstan in 1156 in the

countryside near Ripon. According to manuscripts from the 12th

century, de Kinstan claimed that the Virgin Mary came to him in a

vision when he and twelve other monks who were travelling from

Byland Abbey to an abbey at Fors got lost in a forest.

Apparently she told him to found an abbey at Ure vale instead.

More mundane reasons for the move involve the fact that the abbey

at Fors was in an exposed position, which made it hard to grow

crops, so Roger de Mowbray, their landowner, gave them permission

to set up a monastery in a more sheltered position on his land on

the south bank of the river Ure or Jore. The name Jervaulx is

thought to be a French spelling of Jorevale.

The monks of Jervaulx were famous for breeding good quality

horses and for creating the process for making Wensleydale cheese

-- a process, which, thankfully, they passed on to the local

farmers' wives and which is still being used today.

Jervaulx was almost completely destroyed on the orders of Henry

VIII, as its last abbot was involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace

in 1536. This was an uprising in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire

against Henry VIII's religious policies; its leaders were

executed in 1537.

Despite the efforts to destroy Jervaulx Abbey, we can still

gather an impression of what the abbey was like from the site

today. Most of the church has gone but you can see the

foundations and the remains of a round-headed doorway to the

southwest that is decorated in the Norman dog-tooth style. On

the floor of the church there are several tombstones, including a

stone effigy of one of the abbey's benefactors, Hugh Fitzhugh,

who is portrayed as a knight in armour. The wooden pulpitum

screen was removed to safety in nearby Aysgarth Church where it

can still be seen today.

The chapter house retains five original columns, which give an

impression of the height of the vaulted roof. Large sections of

the infirmary and monk's dormitory remain, including a wall with

nine lancet windows. Finally, at the gate, you will see an

embalming stone, originally housed in the infirmary, and if you

look closely at the house to the right of the entrance, you can

see the stones taken from the gatehouse of the abbey.

Mount Grace Priory

Mount Grace Priory, founded in 1398, is included in our list

because it is the best preserved monastery or charterhouse of the

ten Carthusian monasteries in England. The Carthusians, unlike

the other monks we've looked at, lived a very austere life of

work and prayer as hermits in small, two-storey cells. There

were two rooms on each floor of the cell and each cell had a

garden where the monk could grow some food.

At Mount Grace, the foundations of 23 cells can be seen and one

cell has been reconstructed and furnished to show what it might

have looked like in the 14th century.The church is remarkably

preserved; the tower is intact and most of the walls are still

standing. In the cloister stands the base of the water tower that

was central to the Carthusian monks' water system. The outer

court of the priory is also intact, and much of this has now been

planted with formal gardens and trees and is home to a variety of

birds.

To gain entry to the priory you need to pass through a

17th-century manor house, built on the site of the monastery's

guest house in 1654. This building, however, is not what it

seems, as it was itself rebuilt at the beginning of the 20th

century using techniques from the Arts and Crafts Movement.

If the reasons given above haven't persuaded you that these

particular monasteries merit a visit, then perhaps my final

reason might. Between them these ruins cover the development of

the monasteries from the first Norman monasteries to be built at

the start of the 12th century to the 'modern' monasteries of the

14th century. But, to be honest, even without the history, the

beauty of them alone is reason enough for a visit.

Related Articles:

- Where Emperors, Kings and Saints Have Walked: York Minster, by Julia Hickey

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/minster.shtml

- The Lingering Power of Fountains Abbey, by Julia Hickey

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/fountains.shtml

- Hidden Churches of Yorkshire, by Louise Simmons

- https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/churches/yorkshire.shtml

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Dawn Copeman is a freelance writer and commercial writer who has had more than 100 articles published on travel, history, cookery, health and writing. She currently lives in Lincolnshire, where she is

working on her first fiction book. She started her career as a freelance

writer in 2004 and has been a contributing editor for several publications, including TimeTravel-Britain.com and Writing-World.com .

Article © 2006 Dawn Copeman

Kirkham Priory photo courtey of Wikipedia.org; Rievaulx photo courtesy of Britainonview.com

|