Christmas at the Court of King James I

by Elaine Walker

King James I became the first monarch to rule the whole of the

British Isles with the death of his cousin, Elizabeth I, in 1603.

He had been on the throne for only six months when he hosted his

first Christmas and New Year festivities. The celebrations

offered an opportunity to display his wealth and largesse, with

extensive feasting, dancing and theatrical performances in the

Great Hall of Hampton Court Palace. Among the actors was one

William Shakespeare, whose play A Midsummer Night's Dream

is thought to have been performed on New Year's Day, under the

title A Play of Robin Goodfellow. The whole week would

have been full of colour and inventive entertainment, helping to

establish King James as a gracious and regal host and setting the

pattern for Christmas throughout his reign.

The King's lavish generosity at Hampton Court was part of his

belief in the value of traditional customs, and extended to his

whole household in a measure considered suitable to their status.

He believed that 'certaine dayes in the yeere should be

appointed, for delighting the people, for conveening of

neighbours, for entertaining friendship and heartlinesse, by

honest feasting and merrinesse'. At Christmas, this included the

duty of the wealthy to succour the poor, and the King ensured

that this continued by writing the custom of hospitality on St.

Stephen's Day (Boxing Day) into the law.

Shakespeare's King Lear, which was performed for King

James on St. Stephen's Day in 1606, is full of references to the

care of the homeless on this day. A popular saying reminded

people that 'Blessed be St. Stephen/There's no fast upon his

even'. Shakespeare recalled another favourite Christmas festival

in Twelfth Night, which was performed before King James in

1618 and 1623. The play centres around generosity, love and

change in the disguises, mistaken identities and happy outcomes

for all but the gloomy Malvolio. Malvolio represents the growing

Puritan suspicion of celebratory festivals, especially Christmas,

and the riotous Sir Toby Belch addresses the matter when he asks

Malvolio, 'Dost thou think because thou art virtuous, there shall

be no more cakes and ale?'.

Another popular feature of

Christmas festivities was the Feast of Fools from St. Stephen's

Day until December 28th. This period reminded the Christmas

revellers of the Christian message of hope for the poor and weak,

but was rooted in the pagan tradition of the Lord of Misrule.

Society turned briefly on its head, so that kings could become

fools and fools could become kings. Masques, which King James

particularly enjoyed, developed from this festival of drinking,

games and disorder. Masques were short dramatic entertainments

with music, verse, dancing and elaborate scenic effects and

flourished at court in King James' time. Ladies and gentlemen,

including members of the royal family, appeared in the masques,

along with professional actors. The masques were often written

for a specific event at which the king was to be present, and so

included declarations of love and loyalty addressed directly to

him on behalf of his subjects. Another popular feature of

Christmas festivities was the Feast of Fools from St. Stephen's

Day until December 28th. This period reminded the Christmas

revellers of the Christian message of hope for the poor and weak,

but was rooted in the pagan tradition of the Lord of Misrule.

Society turned briefly on its head, so that kings could become

fools and fools could become kings. Masques, which King James

particularly enjoyed, developed from this festival of drinking,

games and disorder. Masques were short dramatic entertainments

with music, verse, dancing and elaborate scenic effects and

flourished at court in King James' time. Ladies and gentlemen,

including members of the royal family, appeared in the masques,

along with professional actors. The masques were often written

for a specific event at which the king was to be present, and so

included declarations of love and loyalty addressed directly to

him on behalf of his subjects.

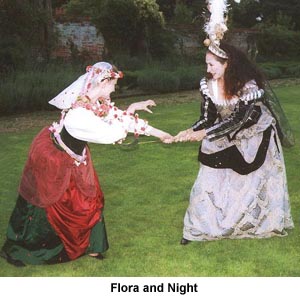

On Twelfth Night in 1607, a masque by Thomas Campion was held at

the Palace of Whitehall in the presence of King James and

detailed notes of the event give an idea of how elaborate these

theatrical performances were. The Great Hall of the palace had

seats on either side with scaffolding for two stages, the lower

one being for dancing. Twenty musicians were involved with lutes,

a bandora, a sackbut, a harpsichord and violins, as well as

singers. The scenery included a double veil, painted to look like

dark clouds over a green valley with nine golden trees, whose

branches were 'very glorious to behold'. At the sides of the

stage, the scenery suggested two hills with decorated bowers for

the characters Flora and Night and a tree belonging to Diana, the

goddess of the Hunt. The set included details such as

'artificialle Battes and Owles on wyer constantly moving'. When

the King arrived, the musicians played until he and his entourage

were settled, then after a 'little time of expectation', the

masque began, with much singing and dancing.

Ben Jonson's Christmas His Masque was written and

performed for King James and Queen Anne in 1616. Early in the

masque, the characters offer prayers for the royal couple's

welfare and pray they will like the performance, for 'If not, old

Christmas is undone'. This placing of the future of Christmas in

the hands of the monarch was prophetic as Christmas festivities

were banned in 1647, after Charles I lost his throne to

Parliament, and not reinstated until the Restoration of the

monarchy in 1660. The ill-fated future king was a young boy in

1616 and is mentioned in Jonson's masque as 'Your highness

small'.

The focus on family, the love of the people for the King and the

celebration of traditional customs are at the heart of Jonson's

masque. The character of Christmas introduces his children, who

include 'Carol', 'Misrule', 'Wassail', 'Gambol' and 'New Year's

Gift'. At this time, gifts were given at New Year rather than

Christmas and each of Christmas's children remind the King and

the audience of the pleasures of the season. What is clear

throughout this masque, however, is the concern that these

traditions are fading away. In his Survey of London in

1603, John Stoye wrote that 'in the feast of Christmas' there

were once 'fine and subtle disguisings, masks and mummeries' and

'every man's house was decked with whatsoever the season of the

year afforded to be green'. While both festivities and decorating

houses with evergreen were still common, Stoye felt that real

enthusiasm for Christmas traditions belonged in the past.

King James,

however, seems to have worked hard to keep them alive at his

court with great feasting and entertainment offered to fend off

the gloom of those who saw Christmas as a time of idolatry and

impious drunkenness. The King's court enjoyed the generous flow

of wine and ale, as well as imported spirits such as brandy and

rum, which were becoming popular amongst those who could afford

them. Christmas ale and mulled wine were also popular with the

people as well as the nobility, to be drunk hot and heavily

spiced. King James,

however, seems to have worked hard to keep them alive at his

court with great feasting and entertainment offered to fend off

the gloom of those who saw Christmas as a time of idolatry and

impious drunkenness. The King's court enjoyed the generous flow

of wine and ale, as well as imported spirits such as brandy and

rum, which were becoming popular amongst those who could afford

them. Christmas ale and mulled wine were also popular with the

people as well as the nobility, to be drunk hot and heavily

spiced.

The food enjoyed at Christmas would have included roast turkey,

goose, game birds and, at court, peacock gilded and served in its

own feathers. Other meats were also popular, with Scotch Collops

being a favourite. 'Collops' were thin slices of meat dipped in

seasoned flour then fried quickly before being immersed in a

richly flavoured casserole with wine, garlic, onions, mushrooms

and anchovies. In Scotland venison was popular in collops, while

southerners preferred ham or bacon. As in many dishes, local

tastes and the available meats decided the precise recipe.

The medieval tradition of the roast Boar's Head was still

popular as a centre-piece for Christmas Day, Twelfth Night or

both, to be carried aloft into the banqueting hall accompanied by

a fanfare of trumpets. Spit-roasting was the usual method for

cooking meat, with complex arrangements for large gatherings,

whereby a number of items could be cooked at once. The spit was

turned with a mechanical jack, wound up with a heavy weight on a

cord wrapped around a drum. As the weight gradually descended,

controlled by a balance wheel, the spit laden with meat or

poultry could be kept revolving for almost half an hour. The

development of the chimney crane, which could raise and lower the

level of pots and cauldrons over the fire, further simplified the

life of the kitchen, a place of great activity at the court.

Plum Pottage was well established by the time of King James, and

on its way to becoming the Christmas pudding of today. It had

begun as a thick soup-like dish of boiled beef or mutton with

dried fruit and plenty of spices. During the seventeenth century

it became a solid pudding without any meat, which eventually

replaced the pottage. Fats, dried fruit and sugars were notable

in this sort of heavy steamed pudding, perhaps because the damp

British climate needed good energy-producing food to keep out the

chill. 'Cambridge' or 'College' pudding, made with suet,

breadcrumbs, flour, dried fruit and eggs typified the sort of

filling dessert that made a foreign visitor declare, 'Ah what an

excellent thing is the English pudding! To come in pudding-time,

is to come in the most lucky moment in the world!' Among these

robust puddings at Christmas were 'shred' or 'mince' pies, still

popular today, which like plum pudding, originally contained both

fruit and minced meat.

Lighter sweet dishes were also popular with the refined court

diners and would have been presented very beautifully for the

King's table. These were rich, based around fruit or sugar, with

exotic fruits like pineapples and bananas beginning to make an

appearance. White Biscuit Bread, flavoured with almonds, lemon,

coriander and aniseed, were very similar to today's meringues,

and this sort of crisp delicacy was a court favourite.

'Scillybub', 'raspbery creame', and white-pot, an ancestor of

bread-and-butter pudding, all featured on the table, with an

emphasis on indulgent ingredients, with plenty of eggs and cream.

All of these dishes and many more made their appearance

at Christmas and New Year in the court celebrations of King James

I. The generosity of the monarch showed both that he could be

lavish with his subjects and that he had the wealth to entertain

them so freely. As with many of the Christmas traditions,

open-handed giving, charity, welcoming the homeless and offering

alms to the poor both broke down and reinforced social boundaries

in the same moment.

With so much feasting, the dancing must have provided a

welcome activity and Queen Anne was known for her enjoyment of

the dance floor. Dancing at court or as part of the Christmas

celebrations was not new and while the Queen was criticised by

some for her love of such pleasures, she would have understood

very well the political importance of these events. Her

willingness to take part with grace and enjoyment was part of the

welcome offered to foreign ambassadors, as well as a sign of the

royal appreciation of the court which supported the role of the

monarch. The delicate relationships of the court could be

nurtured through the King's largesse during events such as

Christmas, so as well as the sentiments of the season, some

astute political balancing would undoubtedly be going on too.

While the Jacobean Christmas was poised on the edge of a time of

great uncertainty and change, the sense of celebration and the

hopes of the new Stuart dynasty were still high during King

James' reign. So, despite concerns over the growing religious

controversies that would eventually split the kingdom, Christmas

still held an important place as a time of celebration,

hospitality and community spirit. Some of the medieval traditions

were slipping away, but decking the halls with evergreens,

sharing fine food and drink, and enjoying music and dancing still

offered the opportunity to celebrate an important Christian

festival. There was a sense of abandoning cares for a short time

which is embraced in the sentiments of a popular song which

declared,

Though some churls at our mirth repine,

Round your foreheads garlands twine,

Drown sorrow in a cup of

wine,

And let us all be merry

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

|

Dr. Elaine Walker is a freelance writer based in North Wales. She writes fiction, poetry and nonfiction and lectures in Creative Writing and English for the University of Wales. Her first full-length book, Horse, is forthcoming from Reaktion Books in Autumn 2008.

|

Article © 2005 Elaine Walker

Photos courtesy of Passomezzo.

|