St. Paul's Cathedral

by Helen Gazeley

What makes St Paul's a "must-see" for visitors to London? Certainly it has influenced architecture around the world, from the Pantheon in Paris to Baltimore Cathedral, but this wouldn't be enough to make it, according to a recent survey, the best loved building in Britain. Somehow, it's come to represent Britain in a way that even the Houses of Parliament can't quite match, and one has to delve into the history to find out why.

Standing in front of St Paul's now, it takes effort to imagine the scene before the Great Fire. At the end of August 1666, the City of London was still medieval, "a congestion of mis-shapen and extravagant houses", as the diarist, John Evelyn, put it; a jumble of tiny alleys. The upper storeys of the wooden houses pressed so close that in places it was impossible to see the sky; drainage was often an open ditch down the middle of the street. The enormous old cathedral of St Paul's, with a nave 1600 feet long, towered above the surrounding area, described by Evelyn as "comparable with any in Europe"; a source of pride but in desperate need of repair.

By September 6th, four fifths of the City had gone: over 13,000 houses and 87 parish churches lay smouldering, the debris so thick that the streets beneath were invisible. St Paul's, from which the lead had run from the roofs in streams as the fire took hold, was so devastated that it seemed "like some Antique Ruine of 2000 years continuance".

But from these ruins rose what is today one of Britain's most recognised landmarks. Wren had wanted to put a dome on the old St Paul's even before the Great Fire, when he was appointed to advise on renovations. He wanted the same for the new building, explaining it as a "noble cupola, a forme of Church-building, not as yet known in England, but of wonderful grace."

The design of the cathedral we see today was, however, never officially approved. Christopher Wren -- summoned, when it was realised the old building could not be saved, by the Dean of St Paul's with the words, "What we are to do next is the present Deliberation, in which you are so absolutely and indispensably necessary to us that we can do nothing... without you" -- offered two designs before a third was accepted by royal warrant. The first two are on display in the Trophy Room on the Triforium level. The second design, represented in the Great Model, twenty feet long and made of oak, is well worth seeing. It is said that he cried when the clergy rejected it.

The third, the "Warrant Design", was extraordinary, sporting a huge spire echoing the one which had fallen from old St Paul's in 1561, and it's possible that Wren submitted it in exasperation. The building today bears little resemblance to it. Cunningly, he had it agreed that he could "make variations, rather ornamental than essential" and he stretched this clause considerably, erecting screens around the building site partly to hide the changes made. Wren didn't get everything he wanted, but he certainly got the dome that had previously been refused.

The work was well-starred from the outset. When building began in 1675, Wren sent a workman for a stone to mark the spot which would be immediately beneath the dome. The man brought a fragment on which was inscribed the single world "Resurgam" (I shall rise again). When you pass the south door, check the pediment, where Wren had this word carved beneath a phoenix rising from the flames. The work was well-starred from the outset. When building began in 1675, Wren sent a workman for a stone to mark the spot which would be immediately beneath the dome. The man brought a fragment on which was inscribed the single world "Resurgam" (I shall rise again). When you pass the south door, check the pediment, where Wren had this word carved beneath a phoenix rising from the flames.

The new St Paul's drew every visitor in the City. With the second largest dome in the world after St Peter's, Rome, it was rapturously received as a Renaissance masterpiece, its influence reaching even the coffee-pots of the Queen Anne period, with their domed lids.

Since then, like the old cathedral before it, St Paul's has remained at the heart of civic and State life. Perhaps best known in recent years as the venue for the marriage of Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer in 1981, its services have marked the nation's anxieties and joys. Services of thanksgiving have been given for the recovery of the monarch from grave illness: George III in 1789 (sadly not to last), Edward VIII in 1902 (whose illness had postponed the Coronation), George V in 1929. Services have marked the end of war: the first service held in 1697 was in thanks for the peace with France and 35,000 people attended the ten simple services to give thanks for the end of World War II; and also the continuance of reigns: George V's Silver Jubilee in 1935, the present Queen's in 1977, and her Golden Jubilee in 2002.

In the pavement just in front of St Paul's is a plaque, marking the spot where Queen Victoria sat in her carriage in 1897, while a Service of Thanksgiving for her Diamond Jubilee, "Sixty Glorious Years", took place before her on the steps which she herself was unable to climb. In her journal she recorded the dense crowds, writing, "It was like a triumphal entry." Nearing St Paul's, the procession stopped often and the crowds broke out into the National Anthem. And she arrived at the west front of the cathedral to find "All the Colonial troops, on foot, ...drawn up round the square."

Her carriage had to negotiate the statue of Queen Anne (1702-1714), still there today. It had been proposed that this should be moved to make a clearer approach but she refused to allow it. "One day," she said, "there will be a statue of me in London and someone might want to move that -- and I should not like that at all."

This showed more regard for the last of the Stuart dynasty than many had had at the time. The statue, dating from 1886, is a copy replacing the badly worn original put there in 1712 to commemorate the completion of the cathedral. In 1714, Anne's death brought about the Hanoverian succession because none of her 17 children had survived. This, and her reputed liking for strong drink, were satirised in contemporary rhyme:

"Brandy Nan, Brandy Nan,

You left us in the lurch,

Your face towards the brandy-shop

Your arse to the church."

No visits to St Paul's can miss the crypt. This includes the tombs of great artists and musicians and many distinguished sailors and soldiers, but only two of these were honoured with a State funeral at the cathedral. Tempting though it is arrive at St Paul's Underground Station to visit, try to make the approach up Ludgate Hill to the west front, for this is the route of State processions. In January 1806 Nelson's body arrived on a carriage shaped like his ship, the Victory, passing huge crowds from which the only sound was a soft murmur, like that of the sea, as men removed their hats.

On the morning of 18th November 1852, the crowds awaiting the Duke of Wellington's coffin were so dense around St Paul's that the lamplighters couldn't reach the streetlamps to turn them off. When his coffin arrived on its monstrous carriage, proceedings were held up for an hour as the bearers tried to figure out how to move it, fifteen feet above them, on to the waiting bier. Thousands of mourners, seated in specially built stands in the nave, suffered as the freezing wind swept through the open West door.

Nelson's funeral lasted four hours, dramatically lit by a chandelier of 130 lamps: a beacon in the surrounding gloom of the crossing. The same lighting was attempted at Wellington's funeral, but the sun came out and spoilt the effect. On that occasion, there were so many thousands of people crammed into the cathedral that their simultaneous turning of the pages of the order of service produced a dull roar "such as a sudden gust causes in a forest in autumn".

At the end of both these funerals, the coffin was let down through the floor of the cathedral into the crypt. At this solemn moment in 1806, instead of reverently furling the Victory's battle ensign, leaving it ready to be placed in Nelson's coffin, the sailors unexpectedly ripped pieces out of it and stuffed them in their pockets as keepsakes. At Wellington's descent, the Marquess of Anglesey "stepped forward and, with tears streaming down his cheeks, placed his hand upon [the coffin] in a moving gesture of farewell."

It was not until 1965 that another hero was honoured at St Paul's. At Sir Winston Churchill's funeral, the congregation might have been restricted to a more manageable 3000 in number, but it included 6 monarchs and 15 heads of state. It seems particularly appropriate that Churchill's funeral was held here for it was, perhaps, the Second World War that cemented St Paul's so firmly in the nation's heart. There are mementoes of this period around the cathedral.

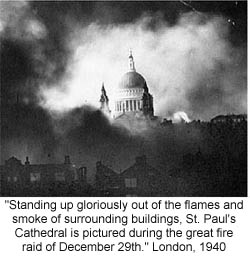

Between September 1940 and May 1941 hundreds of thousands of high explosive and incendiary bombs fell on the City. On the night of 29th December 1940 alone, 8 churches by Wren were lost, but St Paul's miraculously escaped. More than once it could have been different. The high altar was destroyed by a bomb falling through the quire in October 1940; another fell in the north aisle in April 1941; and in September 1940 a 2,200lb monster failed to detonate just to the right of the front steps (about 20 feet out from the south tower, near the last bollard) but, after being gingerly dug up and transported to the "bomb graveyard" in Hackney Marshes, left a crater 100 feet across on detonation. Between September 1940 and May 1941 hundreds of thousands of high explosive and incendiary bombs fell on the City. On the night of 29th December 1940 alone, 8 churches by Wren were lost, but St Paul's miraculously escaped. More than once it could have been different. The high altar was destroyed by a bomb falling through the quire in October 1940; another fell in the north aisle in April 1941; and in September 1940 a 2,200lb monster failed to detonate just to the right of the front steps (about 20 feet out from the south tower, near the last bollard) but, after being gingerly dug up and transported to the "bomb graveyard" in Hackney Marshes, left a crater 100 feet across on detonation.

That the cathedral escaped was thanks to the St Paul's Watch. This band of 200 volunteers, many recruited from the Royal Institute of British Architects, knew the building inside out. They worked tirelessly, sometimes risking death by falling as they crossed rafters to reach wayward firebombs. After a particularly exhausting night in April 1941, one wrote: "Eight solid hours fighting to save St Paul's. We put out every sort of fire... but couldn't cope with the terrific H.E. [High Explosive] crashes... It rocked so much once we were sure it was over."

On 29th December 1940 it was touch and go. An incendiary broke through the dome. Edward R. Murrow, the American correspondent, saw the fire and announced on air, "the church that means most to Londoners is gone. St Paul's Cathedral... is burning to the ground." But it wasn't. With the Thames at low tide and the water-mains broken, the firewatchers had to resort to stirrup pumps, buckets and sandbags, but they prevailed. On that night was taken the famous photo of the dome above billowing smoke as the City burned. More than anything else, St Paul's seemed to represent Britain's own lone stand against the enemy. On 29th December 1940 it was touch and go. An incendiary broke through the dome. Edward R. Murrow, the American correspondent, saw the fire and announced on air, "the church that means most to Londoners is gone. St Paul's Cathedral... is burning to the ground." But it wasn't. With the Thames at low tide and the water-mains broken, the firewatchers had to resort to stirrup pumps, buckets and sandbags, but they prevailed. On that night was taken the famous photo of the dome above billowing smoke as the City burned. More than anything else, St Paul's seemed to represent Britain's own lone stand against the enemy.

Today St Paul's is still a vibrant part of city life. Concerts and recitals are held every week, and ancient civic ceremonies are still enacted annually by the City's guilds. You might like to time your visit to end in time for Evensong at 5.00 pm (Mon-Sat). Alternatively, you could take time, as Wren liked to do until his death in 1723, at the age of 91, just to sit under the dome and revel in his masterpiece.

Opening times: Monday-Saturday from 8.30 am to 4 pm. Sometimes the cathedral has to close at short notice, so you should always check the diary. The cafe in the crypt is open 9-5 Monday-Saturday, 10-5 Sundays; the restaurant 11.30-5 everyday. The entry fee is £10 per person, and no photography is permitted.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Helen Gazeley is a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in the Daily Telegraph, Artists and Illustrators, Organic and Healthy Living and Kitchen Garden Magazine. She also writes a regular column for Organic Gardening. London and eating are two major enjoyments, so she knows a decent place to eat near any major attraction.

Article © 2005 Helen Gazeley

West Front and Firefighter's Memorial courtesy of Helen Gazeley;

additional photos courtesy of Wikipedia.org

|