Chatsworth House: A Palace for "A Woman of Much Address"

by Mike Wendling

It's a shame to approach it, as most people do, by car. Ideally you'd like to come on horseback, or maybe by carriage. Or even by foot, in late autumn or early spring after a day's journey through mud and light snow -- as this is a part of England that is, despite global warming, north enough and high enough to still catch significant quantities of the white stuff.

So no, car is not the ideal way to get to Chatsworth House. Drivers are cheated by having to look at the road; passengers can only snatch brief glimpses of the solid yellow-tinged main building and the sweeping bridge in front. Today the house is thoroughly well preserved, and fitted with modern conveniences, but it doesn't take a giant leap of imagination to picture the grand characters and high royalty that were once the exclusive inhabitants of this stately palace in the Derbyshire countryside.

Sir William Cavendish first settled in the area from Suffolk in Eastern England in 1549 and the building of the manor commenced three years later. Cavendish made his fortune in the service of Henry VIII, splitting up monasteries and helping to destroy the hold that the Catholic Church had on religious life in England at the time.

But the driving force behind the original Chatsworth House wasn't the loyal servant Sir William but rather, his wife, Bess of Hardwick. Bess was an upwardly mobile local girl who persuaded her new husband (Sir William was the number two of four) to sell off some of his other lands and settle in Derbyshire. She was a controversial figure, and although it would be left to her descendants to claim the titles of Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, she is the true matriarch of the Cavendish family. A contemporary account described her as "a woman of much address, had a mind admirably fitted for business, very ambitious, and withal overbearing, selfish, proud, treacherous, and unfeeling; one object she pursued through a long life, to amass wealth and to aggrandise her family. To this she seems to have sacrificed every principle of honour or affection; and to have completely succeeded."

Of the original house, only the Hunting Tower, which stands on a hill behind the house, still stands. Sir William died in 1557, having hardly been able to enjoy the delights of his new manor. Bess eventually married George Talbot, the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. Shrewsbury was named by Queen Elizabeth I as the custodian of her rival, Mary Queen of Scots, and from that point on, the inhabitants of the house have been intrinsically tied up with the history of Britain.

Mary was a prisoner in the house on and off from 1569 and 1584. You won't feel too sorry for her, though, when you see her sumptuous lodgings. It has been said -- but not exactly confirmed -- that Mary and Bess spent many hours in these rooms doing needlepoint together.

Visitors with a further interest in Bess of Hardwick would be well advised to make a side trip to Hardwick Hall near the town of Chesterfield, about 35 minutes away by car. It survives to this day largely in its original condition.

Bess's second son by Sir William, also called William, became the male heir after the death of an older brother. William Junior was made an Earl by the king, starting the Cavendish family's upwardly noble trend.

The younger Cavendish helped give a financial boost to the (at the time) nascent colony of Virginia, and by this time he died the family was well established in the realm of domestic and foreign affairs. His son, the 2nd Earl, married the daughter the Scottish ambassador to England and supported the ascension of James I to the English throne in 1603. The Second Earl's wife was also a great patron to writers, some of whom still have their books preserved in the house today.

The 4th Earl was made a Duke in 1694 after helping hoist William and Mary to the throne. He returned home and promptly became construction-happy. He took down one side of the house, built new rooms to receive the royal couple and found that he had come down with a serious case of home improvement fever. It was during this period that Chatsworth began to take on the stateliness and solidity that it retains today, and work on the house it helped establish the leading British architects of the time. In 1707, just after he was finished with his radical plans, the 1st Duke, exhausted from the work, died.

Being vast landowners and trusted lords, the Cavendishes could not escape politics; indeed, several of Bess's descendants served at the highest levels of the British government. The 3rd Duke (1698-1755) served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and served in the House of Commons until the death of his father catapulted him into the House of Lords. His son, the 4th Duke, also ruled Ireland and for a brief time was Prime Minister.

The early Dukes also fostered the family's great tradition of patronage in the arts and science. The 1st Duke called on Thomas Hobbes to teach his children, while Henry Cavendish (1731-1810), a grandson of the 2nd Duke, determined the composition of water and established hydrogen as an element -- very fitting, considering the large role fountains and springs play in the composition of Chatsworth's gardens. The bulk of Henry's vast book collection is still at the house.

At this point in the family tree, however, came the most colorful Cavendish couple since Bess and Sir William. The 5th Duke (1748-1811) was much more interested in ladies than politics and to this end kept both a wife, Lady Georgiana Spencer, and a mistress, Lady Elizabeth Foster. If you're thinking the name Spencer sounds familiar, you're right -- Lady Georgiana was a great-great-great-great-aunt of Princess Diana.

Although the trio spent most of their time in London, Chatsworth was the site of more than a few drink- and drug-fuelled parties. Georgiana seduced her husband's friends (while her husband was seducing hers), and historians continue to debate the ins and outs of her relationships with her the 5th Duke and his mistress. The details of this titillating mŽnage ˆ trois were most recently depicted in the acclaimed book Georgiana: Duchess of Devonshire by Amanda Foreman.

Although he presided over a house of debauchery, it was during the 5th Duke's adult life that Chatsworth started to show its face to the outside world. The Duke and his wife invited over prominent writers and politicians and held fantastic dinners when they were visiting the countryside from London. Indeed, Chatsworth captured the imagination of artists and guidebook writers from its earliest days. In later years, Daniel Defoe was a frequent visitor, and Jane Austin renamed the house "Pemberley" in Pride and Prejudice.

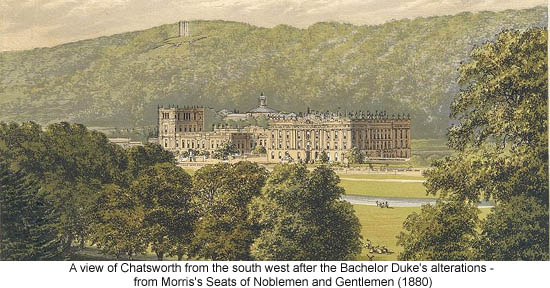

Work on the house continued under the son of Georgiana and the 5th Duke. The 6th Duke was nicknamed the "bachelor," as he never married, but he took a keen interest in gardens and architecture. He befriended gardener Joseph Paxton, who set out the magnificent present-day landscaping, the 300-feet-high Emperor Fountain, and the Great Conservatory, which became a forerunner of Paxton's Crystal Palace in London's Hyde Park. Unfortunately for us, the conservatory became derelict and was torn down soon after World War I.

Throughout the 19th century the Dukes continued to improve the estate as they kept their prime position in the nobility and their interest in politics. The first half of the 20th century, however, was not a great time for country homes in general. Chatsworth did not escape the overall trend, though it still remained useful. During World War II the House was occupied by a residential girls' school.

Once England hoisted itself out of the morass of war and economic decline, the 11th Duke set about improving his ancestral home. It's universally acknowledged that he succeeded, ushering in a new era of restoration and -- just as important -- public access. The 11th Duke, who passed away last year, lived with his family on two floors of the house, and he insisted that no public funds go towards the upkeep of the house and grounds, other than what could be raised by entrance fees and sales from the house's gift shop. His wife, under the title the Duchess of Devonshire, gained renown in Britain through a popular cookbook and other writings on country life. The house is currently open from mid-March to late December, a policy that is set to continue under his son, the current and 12th Duke. Once England hoisted itself out of the morass of war and economic decline, the 11th Duke set about improving his ancestral home. It's universally acknowledged that he succeeded, ushering in a new era of restoration and -- just as important -- public access. The 11th Duke, who passed away last year, lived with his family on two floors of the house, and he insisted that no public funds go towards the upkeep of the house and grounds, other than what could be raised by entrance fees and sales from the house's gift shop. His wife, under the title the Duchess of Devonshire, gained renown in Britain through a popular cookbook and other writings on country life. The house is currently open from mid-March to late December, a policy that is set to continue under his son, the current and 12th Duke.

Today, it's easy to see why a magazine just labeled this house "Britain's Best Stately Home." Much of Chatsworth's magic comes from the fact that it's set down within the Peak District National Park, near the River Derwent and within a 35,000 acre estate. The landholdings are so massive that they stretch across two counties (both Derbyshire and Staffordshire) and support an extensive local economy that's a mix of agriculture, tourism and light industry.

Once inside the house visitors will notice that the building's various designers have done their best to welcome the outside in through plenty of glass and gilt-edged windows. The art collection alone is worth a visit, including a variety of works from the ancients to the present day. Highlights include works by Rembrandt, Gainsborough and Lucian Freud and a rare original edition of The Birds of America. Visitors are able to see the Library, Painted Hall and Great Dining Room, where the very first event held was a dinner party for Princess -- later Queen -- Victoria in 1832. Perhaps the oldest surviving room is the chapel, which was built by the 1st Duke and remains pretty much the same today.

The perfect end to a visit involves -- depending on how energetic you feel -- either a calming rest in the courtyard or an exploration of the 1,000 acre park surrounding the house. And on the way back down (that is, if you haven't already decided to walk), you should now know enough to creep along, ignoring the line of traffic behind you, and to imagine that you're an Austin or a Defoe, disappearing for the evening on your horseless carriage, heading back into town content from time spent in one of England's finest country manors.

Getting There:

Chatsworth House is 16 well-signposted miles from the M1 (exit 29) and 8 miles north of the village of Matlock on the B6012. Travel time is around 30 minutes from the nearest large city, Sheffield. Parking is free at the southern end of the grounds and £1.50 closer to the house.

The closest train station is Chesterfield (14 miles), where direct trains stop from London and Manchester.

Direct bus services operate from Sheffield, Matlock and Bakewell, with a connection from Matlock to Derby; however, the house's website has links to a variety of accommodation close by, and there are B&Bs too numerous to mention in the Peak District.

The house is open from mid-March to late December. A house and garden ticket is £10.00 for adults and £4.00 for children, a garden-only ticket is £5.50/£2.50. Various senior discounts and family passes are available. The house is open from 11:00 a.m. until 5:30 p.m., with the last admission at 4.30 p.m.

In addition to that which is listed above, the grounds also contain a farm yard, farm shop and adventure playground for children.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Mike Wendling is a journalist and writer who has traveled extensively throughout Britain and Europe. He currently lives in London.

Article © 2005 Mike Wendling

Photos courtesy of Britainonview.com

Engraving courtesy of Wikipedia.org

|