Romsey Abbey: A House Divided, a House Preserved

by Moira Allen

Sometimes, being a "house divided" is not such a bad

thing! In the case of Romsey Abbey in Hampshire, it proved that

house's salvation. Sometimes, being a "house divided" is not such a bad

thing! In the case of Romsey Abbey in Hampshire, it proved that

house's salvation.

Romsey Abbey was founded in Saxon times as a nunnery, but rebuilt

in Norman times to house not only the convent and its church, but

also the local parish church of Romsey. The convent occupied the

southern section of the building, while the parish church

occupied the northern side. Hence, when the abbey was

"dissolved" by Henry VIII in 1539, the town was in peril of

losing its only house of worship, and so the townsfolk were able

to successfully petition Henry to sell the building back to them

for £100. And so, instead of being sold off to one of

Henry's lords to become, at best, a manor, or at worst, be

stripped of its building stone, Romsey Abbey survived not only

intact but as a religious house.

The Saxon abbey was founded by King Edward the Elder, son of

Alfred the Great, around 907 AD. He established a convent of 100

nuns, with his daughter Elfleda as abbess. It is likely, however,

that there was already a religious centre on this site long

before the abbey was founded.

The abbey's early life was far from settled. Vikings frequently

raided the region, causing the nuns to flee to the safety of

nearby Winchester on more than one occasion. Perhaps more

detrimental, however, was the hostility of King Eadwig (953-959)

to the church. Eadwig was succeeded by his brother Edgar, who

complained:

All the monasteries in my realm, to the outward sight, are

nothing but worm-eaten and rotten lumber and boards; and what is

worse, they are almost empty and devoid of divine

service.

Edgar rebuilt and endowed at least 40 monasteries, including

Romsey, and united them under the Rule of St. Benedict (until

that time, monasteries in England could choose whatever rule they

wished). When his young son died, Edgar had him buried at Romsey

Abbey.

The Norman building was begun in 1120, and completed about a

century later. The building was probably sponsored by Henry I,

though no records exist to confirm this. Henry, however, had a

strong connection to the abbey through his wife, Queen

Matilda.

Matilda, who was originally known as Eadyth, was the daughter of

Queen Margaret of Scotland and a direct descendant of the Saxon

royal line. William II, son of William the Conqueror, visited

Romsey Abbey with an eye toward marrying Eadyth and hence

annexing the Saxon royal line to his own -- which would have been

a sound political move. Eadyth, however, was in the care of her

aunt Christina, a nun at the abbey, and Christina had other

ideas. She had no intention of letting her niece marry a man of

William's dissolute reputation; William was at odds with the

church for most of his reign, and was, according to the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "hated by almost all his people." So, the

story goes, when William entered the abbey gardens to get a

glimpse of Eadyth, Christina threw a veil over the girl's head

and declared that she was already a nun. Apparently William

wasn't all that keen on the marriage anyway, and he didn't press

the issue.

Shortly thereafter, William was shot with an arrow while

hunting in the New Forest, and his brother Henry assumed the

throne. He, too, saw the advantages of a marriage to Eadyth and

proposed -- and apparently Christina considered him a more

acceptable candidate. The only problem was that the story had

now gotten about that Eadyth had taken vows as a nun and could

not marry. Finally Eadyth herself wrote a letter to Archbishop

Anselm, stating that she had never taken vows or willingly worn

the veil. Her words must have been convincing, as Anselm himself

performed the wedding ceremony. Henry was not noted to be the

most faithful of husbands, but was heartbroken at her death in

1118 -- a death followed two years later by the loss of his son,

William, in the sinking of the White Ship.

The new Norman building was erected upon the same site as the old

Saxon building, and exhibits a wide range of styles, from Saxon

to Gothic. The visitor can't help but note that no two columns

seem precisely the same -- and some variations may simply

represent the whims of the architects. Of course, the building

has undergone many changes and revisions since its original

construction; a new roof was provided by Henry III, who

contributed oaks from the New Forest for its building, while the

present barrel roof dates from the 1860's. In the 1400's, the

north aisle was no longer sufficient to serve as the parish

church for the local population, so William of Wykeham granted

permission for it to be enlarged. The abbey once had a separate

bell tower, but this fell into disrepair after the Dissolution,

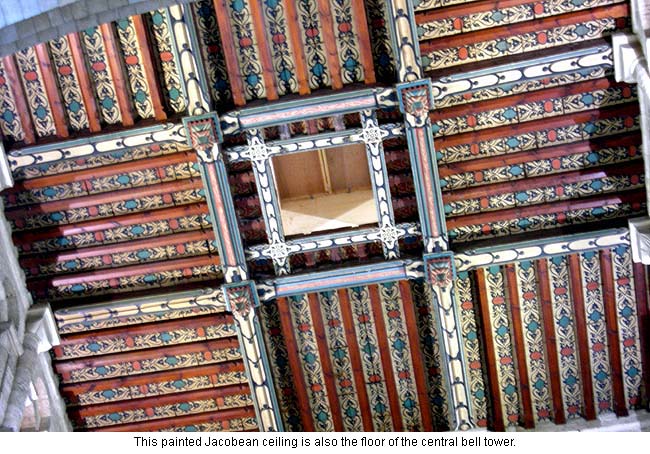

and a new central bell tower was erected; one can look up at a

lovely painted Jacobean ceiling that serves as the bellringers'

floor.

A House of Saints and Sinners

The early abbesses of

Romsey abbey were noted for their piety, and the abbey

contributed several saints to the Catholic roster, including

Merwenna, abbess during the reign of King Edgar. Most famous,

however, was Ethelfleda, the orphaned daughter of one of Edgar's

nobles and Merwenna's ward. Many miracles were attributed to

Ethelfleda; it was said that she could read the scriptures by

night by the glow that emanated from her fingertips. On one

occasion, she gave away the abbey's funds to the poor, yet the

treasury was miraculously refilled the next morning.

The convent flourished at least until the 14th century; in 1311,

the bishop decreed that it had too many nuns and could take no

more until its number returned to "normal" (possibly the 100 that

had originally been established). When the Black Death swept

England in the mid-14th century, however, the abbey was hit

hard; by 1478, only 18 nuns remained, and the number never rose

above 25 thereafter.

According to many historians, the abbey's population declined not

only in quantity but in quality. While nuns of the Saxon and

early Norman period generally had a genuine vocation, by the

Middle Ages convents had become a convenient place to dispose of

inconvenient women. Here, families could leave daughters who

were unlikely to attract husbands due to lack of looks, lack of

dowry, or mental or physical defects. Husbands could confine

unfaithful (or simply unwanted) wives to a convent, and many

widows had nowhere else to go. Guardians of heiresses often

confined such children to convents as well, in hopes of

inheriting their wealth if and when they took the veil.

In addition, by the Middle Ages, education was no longer

considered essential for a well-born lady. Hence, while Saxon

ladies like Eadyth could read and write in more than one language

(Eadyth wrote her letter to Anselm in Latin), and Norman ladies

could at least read French, by the 14th century many nuns no

longer understood the Latin offices. In 1311, a bishop had to

translate his Latin instructions into Norman French, and in later

years few nuns even spoke that.

The rule of St. Benedict focused upon a balance of prayer, manual

labor, and study and meditation. Sadly, the well-born ladies of

the Middle Ages were ill-suited for any of these occupations.

Besides lacking the education to enable them to spend time in

study, they also had virtually no experience with (or interest

in) manual labor. Their hours must have seemed endlessly tedious

-- and nuns were recorded as attempting to alleviate their

boredom with such diversions as fine clothing and pets. On more

than one occasion, nuns were rebuked for bringing their pet dogs

to the services, and Abbess Walerand (1268-1298) was forced by

the Archbishop to give up her pet monkeys and was told she could

have no more than one dog -- and one maid! As early as 1138, a

church council forbade the wearing of furs, including squirrel,

ermine, marten, sable and beaver; in 1200, the wearing of

coloured headdresses and jewelry was also forbidden. Such

restrictions seem to have either lapsed or been ignored over

time, however, since one Agnes Harvey was bequeathed a red mantle

by the vicar.

Such troubles helped provide Henry VIII with an "excuse" to

disband the monasteries, though his primary goal was simply to

seize the vast wealth held by the church. Elizabeth Ryprose, the

last abbess of Romsey, made a last-ditch attempt to save the

abbey by having Henry reconfirm its charter, but she soon saw the

proverbial handwriting upon the wall and arranged to pension off

most of the abbey's servants and officials. Nothing else is

known of her fate or that of the remaining nuns, save one Jane

Wadham, who married the abbey chaplain, claiming that she had

been forced into the convent and did not feel bound by her vows.

Through this marriage, Jane became an ancestress of the St. Barbe

family, whose memorial can be seen in the abbey and whose lands,

Broadlands, have been closely associated with the Abbey over

time.

History in Nooks and Crannies

When you step into Romsey Abbey, you feel as if you are stepping

back in time. The building is quiet, with a pervading sense of

peace; one has no difficulty believing that God has been

worshipped here without interruption (though not, of course,

without controversy) for more than 1000 years. The building has

an almost Byzantine appearance, both inside and out; its massive

columns dominate the small space.

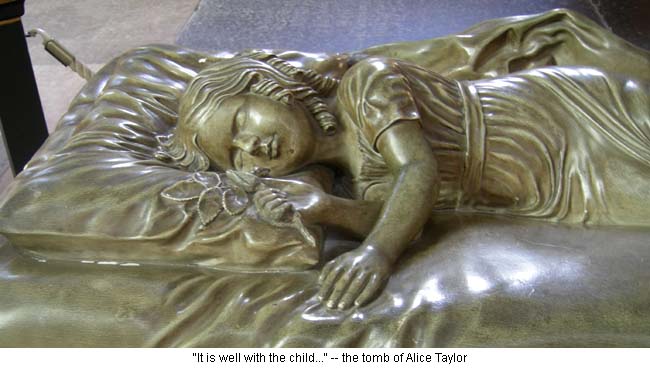

As you enter, one of the first things you'll see is the lovely

sculpture of a sleeping child. This is one of the abbey's most

noteworthy tombs: the resting place of Alice Taylor, who died of

scarlet fever in 1843 at the age of two. Her father, a local

doctor, was also a sculptor, and designed this tomb, inscribed

with the words, "IS it well with the child? It is well." (II

Kings 4:26).

Conversely, the tomb that is most widely advertised in

association with the abbey, that of Earl Mountbatten (who was

assassinated by a terrorist in 1979) is nothing more than a

concrete slab in the floor, beneath the far more striking St.

Barbe monument. The St. Barbe family owned the nearby manor of

Broadlands; the tomb depicts the busts of John St. Barbe and his

wife Grissell, who died within hours of each other in 1658 of a

"sweating sickness." The couple's four sons are depicted below;

one, Henry, had already died when the tomb was built, and of the

others, only one survived to adulthood. After his death,

Broadlands passed to another branch of the family and was

eventually sold; it was finally inherited by Edwina, wife of Earl

Mountbatten, who was the great-grandson of Queen Victoria and

Admiral of the Fleet. Broadlands is now owned by Mountbatten's

grandson, Lord Romsey.

Another striking tomb is that of Sir William Petty. Petty, a

friend of Samuel Pepys, was a scholar and inventor; he studied

languages, arithmetic and astrology, and developed a mechanism

for "double writing" (enabling one to write an original and a

copy at the same time). He dabbled in a variety of business and

managed to make a number of enemies; when one of these challenged

him to a duel, Petty, being nearsighted, suggested hatchets and

axes in a dark cellar. His opponent declined. Petty died in

1687 and is actually buried under a simple slab in the south

aisle, not in the Carrera marble tomb erected in 1858.

In the north transept, one can see the lids of the coffins of

three unnamed abbesses from the 13th and 14th centuries. One lid

depicts the hand of the abbess pushing open the coffin, grasping

her staff; on another, one sees a hand holding the staff. The

images and lettering on the third have almost completely worn

away.

One of the abbey's oldest artifacts is the Saxon "rood" or

crucifix, which now stands upon the altar of the St. Anne chapel

in the south aisle, framed with part of a 15th-century oak

screen. The carving, once richly ornamented with gold and

jewels, depicts Christ upon the cross, flanked by Mary and John.

Two angels perch upon the arms of the cross, waiting to escort

Jesus to heaven; two Roman soldiers stand below, one holding up a

sop of vinegar, the other thrusting a spear into Christ's

side.

One of the abbey's strangest artifacts can be seen in a

glass case near the entrance and the gift shop: a plait of hair,

found within a lead coffin unearthed in 1839 during renovations

to the Abbey. Nothing else remained of the body that had

originally been interred in that coffin, except, the story goes,

a single bone that crumbled to dust when the coffin was open.

The plait appears to be a wig and resembles those of a much later

period, but is believed to predate the abbey's Saxon foundations.

Another unexpected find to occur during renovations was the

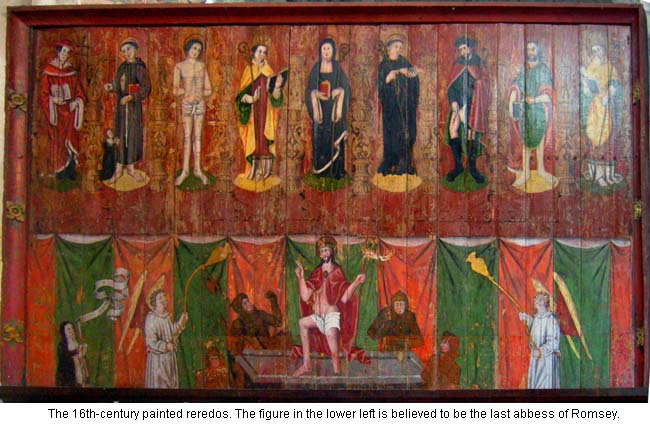

painted reredos that now stands upon an altar in the St. Laurence

chapel in the north aisle. This was discovered in 1813, when the

arches behind the high altar, which had been sealed up for

centuries, were unblocked. The panel had been painted over with

the Ten Commandments; when these were removed, the reredos was

revealed.

The lower half of the reredos depicts the Resurrection, with

angels waving censers and Roman soldiers wearing British plate

armor and carrying medieval poleaxes. An abbess stands to the

left of the scene, presumably the one who commissioned the work

and quite possibly the last abbess of Romsey, Elizabeth Ryprose,

as the panel has been dated to around 1525-1530. The top half

depicts a rather mixed bag of saints, including St. Benedict, St.

Francis, St. Scholastica (patron of nunneries), St. Roche

(pointing toward a plague sore on his leg), St. Jerome, and St.

Armel (with a small dragon). It also depicts two bishops,

including St. Swithun, bishop of Winchester from 852-862 and

patron saint of the diocese. The woman kneeling at the feet of

St. Francis is believed to be Lady Giacoma di Settisoli, a Roman

widow who ministered to the Franciscan brothers.

Another painting to emerge from this same hiding place is that

of a cleric, dating from the 15th century. The figure is

tonsured and wears a grey cloak; the red curtain in the

background is ornamented with flowers, stars and wolves' heads.

It is believed that this may be a pun suggesting the identity of

the figure: Thomas Wolsey (no relation to the cardinal), deacon

of the abbey around 1480. The name "Wolsey" comes from the Saxon

"Wulf-sige" or "wolf victory."

To see one of the most unusual and widely debated features of

Romsey Abbey, one must look up. The capitals of the easternmost

pillars of the north and south choir aisles are "historiated" --

that is, engraved with images that tell a tale. In most

churches, such capitals depict Bible stories, but here, they seem

to depict historical events, though historians can't quite agree

on what those might be.

The north capital depicts the aftermath of a bloody battle, with

decapitated heads, carrion birds snatching up body parts, and a

riderless horse fleeing the scene. In the center stand two kings

with drawn swords -- but angels stand behind each king, grasping

the weapons as if to prevent further bloodshed. One king grasps

the other by the beard. Some historians have noted that touching

a king's beard can represent an act of submission, but no

submissiveness is portrayed here; the first king seems intent on

ripping the second king's beard out by the roots, while the

second grasps the wrist of the first as if to prevent it.

The most commonly accepted theory is that this scene depicts the

Battle of Edington or Ethandune in 878, in which King Alfred

defeated Guthrum the Dane. Guthrum was not killed, and

ultimately accepted baptism with Alfred as his sponsor; the

resulting treaty freed Wessex from Danish rule. There is a

direct connection between the battle and the abbey, as the

battlefield was among the lands granted to the abbey by King

Edgar in 968.

The scene on the second capital is considerably murkier. One

side depicts a seated king and a standing angel holding a scroll

that reads ROBERxT mE fecit ("Robert made me"). In the center,

another figure holds a pyramid or obelisk. On the right are two

more seated figures holding a scroll that reads RobERT TUTE

CONSULe x d s -- a phrase that has yet to be translated

precisely. No one knows who "Robert" is -- whether he was a

patron or perhaps one of the masons. Unlike the kings upon the

other capital, however, these are clean-shaven, suggesting that

they depict Normans rather than Saxons.

Finally, one cannot fail to note the many lovely stained glass

windows in the abbey. Nearly all date from the 19th century,

except for one medieval panel that came from a window in the

church of St. Nicholas in Rouen. This dates from around

1540-1600, and was brought to England in the early 19th century.

The panel depicts the last scene in the journey of the soul:

"Salvation." In this scene, the soul is rising toward heaven,

escorted by an angel and assisted by "Love" (Charitie) and

"Prayer" (Oraison). Remaining earthbound and looking decidedly

disgruntled is the ostentatious almsgiver, holding out some coins

from his purse as if attempting to convince the angel of his

worth.

In a way, this window sums up much of the feel of Romsey Abbey.

Though it has seen scandal, controversy and turmoil over the

centuries, it has remained throughout a house of prayer, with its

eyes set firmly upon heaven -- a house where worship is taken as

seriously today as it was 1000 years ago.

St. Anne's Chapel and Rood |

Romsey Abbey Altar |

Victorian Stained Glass |

St. Barbe Memorial |

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Moira Allen has been writing and editing professionally for more than 30 years. She is the author of seven books and several hundred articles. She has been a lifelong Anglophile, and recently achieved her dream of living in England, spending nearly a year and a half in the history town of Hastings. Allen also hosts the Victorian history site VictorianVoices.net, a topical archive of thousands of articles from British and American Victorian periodicals. Allen currently resides in Maryland.

Article © 2008 Moira Allen

Photos © 2007 by Patrick and Moira Allen

|