Scotland's Midwinter Fire Festivals

by Dr. Gareth Evans

Darkness comes early in the middle of a Scottish winter. At 60o

North in Shetland, the thin December sun struggles low in the sky

from its late 9am rise to its early set, just before 3pm. Even

along the comparatively southern coastline of the Moray Firth,

the day is only about 45 minutes longer. Small wonder then, that

these latitudes host some of the world's most spectacular

midwinter fire festivals, for perhaps nowhere else in the whole

of the British Isles is the summer sun more keenly missed, nor

its return more eagerly awaited.

Such midwinter fires have burned in communities along this

wind-swept northerly coastline throughout history, lit by

successive waves of Picts, Celts, Romans, Vikings and modern

Scots. Though today they are less widespread, those that remain

are truly remarkable spectacles.

The Fireball Ceremony, Stonehaven

The

Aberdeenshire town of Stonehaven provides one of the wildest

welcomes to the New Year to be had at anywhere in Scotland. Each

year at midnight a group of fifty or more of the townsfolk parade

through the main streets to the accompaniment of pipes and drums,

whirling blazing fireballs around their heads by yard-long wire

handles, before finally hurling them into the sea at the harbour. The

Aberdeenshire town of Stonehaven provides one of the wildest

welcomes to the New Year to be had at anywhere in Scotland. Each

year at midnight a group of fifty or more of the townsfolk parade

through the main streets to the accompaniment of pipes and drums,

whirling blazing fireballs around their heads by yard-long wire

handles, before finally hurling them into the sea at the harbour.

The festival itself has been documented since 1910, though it is

possible to trace its direct origins to an earlier 19th Century

fishermen's celebration. It has, however, been suggested that

the ceremony probably dates back to much older pagan purification

rituals using fire to drive out evil spirits, or perhaps to chase

away the "ghost" of the old year. An alternative possibility is

that, like many other midwinter fires, this was originally a

solar celebration marking the start of the sun's return. While it

is impossible to say with certainty, there are distinct

similarities to both of these earlier customs and the whole event

has more than a little pagan feel to it, making it tempting to

believe that the modern festival might indeed be an echo of

pre-Christian rites. Whatever the truth of its own ancestry,

similar ceremonies have been recorded across Europe dating back

to at least the Middle Ages, despite attempts by various Synods

to outlaw such "barbarous heathenry" since the 8th

Century.

The fireballs are constructed from a double cage of stout wire

mesh, packed with a variety of combustible materials, typically

including coal, wood, paper, rags, fir cones and the like, though

the exact recipe comes down to the preference of each individual

swinger. The finished ball then has a strong handle made from a

double wrap of fencing wire firmly fixed to it, before it is

thoroughly inspected and certified safe for use.

The fireball swingers themselves make their appearance a short

time before the clock strikes midnight but the small pipe band is

usually on hand a little while earlier to entertain spectators.

Nowadays these may number ten or twelve thousand strong, but for

a time in the 1960s, with fewer and fewer swingers taking part,

the survival of the festival was uncertain. However, the efforts

of a few staunch local enthusiasts to revive this unique

celebration paid off and today the Stonehaven Fireball Ceremony

remains one of the most impressive spectacles of Hogmanay.

The Burning of the Clavie, Burghead

Seventy miles

north-north east of Stonehaven as the crow flies -- and eleven

days later -- the small village of Burghead on the Moray coast

hosts what is claimed as the oldest fire festival in Scotland and

said to be one of the most ancient in the world. Seventy miles

north-north east of Stonehaven as the crow flies -- and eleven

days later -- the small village of Burghead on the Moray coast

hosts what is claimed as the oldest fire festival in Scotland and

said to be one of the most ancient in the world.

In modern times the blazing clavie is an old whisky cask, but it

would once have been a herring barrel that was filled with wood

and daubed with tar, in keeping with this region of Scotland's

strong link with the sea. What might originally have been used is

open to debate.

It has been suggested that the word clavie may be derived

from the Gaelic cliabh, a wicker carrying basket, though

others propose the Latin clavus meaning a nail, since one

is used to fix the barrel to its carrying post, and traditionally

re-used from year to year. What is clear, is that the true

origins of the Burning of the Clavie, as befits the mythology of

so old a ceremony, have become lost in time, though the festival

has been variously claimed to be Pictish, Celtic, Roman or

Viking.

Today, the clavie is first set alight from a peat taken from the

fire of an old Burghead Provost, and then carried away by the

elected Clavie King. A squad of around ten men, usually

fishermen, take it in turns to carry the burning barrel around

the streets of Burghead, stopping from time to time at the doors

of eminent or favoured residents to offer a smouldering faggot to

bring them luck in the coming year. At the end of the

procession, the clavie is fixed on the ramparts of the old fort

on nearby Doorie Hill, more fuel is added and the resulting

beacon burns bright.

Whatever the real origins of the festival, the modern clavie

burning does offer some interesting historical insights. The

direction of the Clavie King's procession -- clockwise through

the streets -- hints at the same fundamentally solar nature

typical of midwinter fire festivals globally. Whoever first

instigated this celebration -- and the clavie burning has

similarities with all of the suggested pagan traditions -- their

simple fear that the sun would not be reborn and that light and

fertility would not return to the land is clearly evident. Old

superstitions die hard -- and perhaps no where more so than

amongst those who ply the sea for their livelihood. To this day,

fallen embers of the clavie will be snatched up, used to kindle a

New Year fire, kept for luck or sent to friends and relations who

have moved far away from Burghead.

The deliberate distribution of fragments from the ceremonial fire

to re-light hearths is a feature that the Burghead burning shares

with some other ancient, and now largely extinct, fire-festivals.

Despite the attempts of the Scottish church to outlaw the

observance of Celtic feasts, the open-air Beltane celebration --

an early summer fire-festival -- persisted in parts of the

highlands into the 18th and 19th centuries. One of the central

rituals was the kindling of need-fire -- a fire made

without the use of a tinderbox -- which was then used to light

the Beltane bonfires, embers of which subsequently being used to

relight the home-fires which had been allowed to go out the night

before. This idea of need-fire now remains in the midwinter

Burghead Clavie and at one time such festivals were common along

the north-east ports. While it has often been assumed that the

Scottish midwinter fire rituals are hangovers from Norse

tradition, it is equally possible that they represent the

transference of earlier Celtic celebrations to the New Year,

simply to fit in with the modern solar calendar.

A further and perhaps less contentious quirk of history surrounds

the timing. When Pope Gregory XIII issued the papal bull

Inter Gravissimas on 24 February 1582 that introduced the

Gregorian calendar to the world, events were set in motion that

were ultimately to result in Burghead's apparently anomalous New

year celebration. Contrary to what is sometimes suggested,

although in 1600 Scotland followed the Pope's new system in

making the first of January the official start of New Year

(previously 25th March) it was not until 1752 -- along with

England -- that the Gregorian calendar itself was adopted. By

this date, the error between the new dating system and the

earlier Julian model required eleven days to be dropped, thus

explaining why the "old" Scottish New Year, celebrated by the

burning of the clavie, has fallen on the 11th January ever

since.

Once almost certainly a small local event, and one repeated all

along the gale-lashed North Sea coastline, the Burning of the

Clavie at Burghead has grown into a much grander affair. Despite

being damned by the Presbyterian establishment as "idolatrous,

sinfule and heathenish" and officially banned in 1704, each

year large numbers of visitors join the inhabitants of Burghead

in celebration.

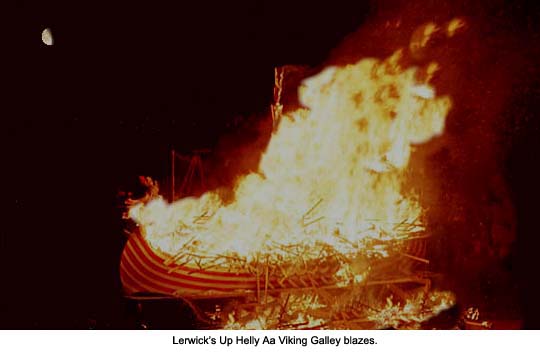

Up-Helly-Aa, Shetland

Possibly the best known of the Scottish midwinter fire festivals,

Shetland's Up-Helly-Aa, which takes place on the last Tuesday in

January each year, is also probably the most visually striking

and evocative, with a flaming longship and a horde of latter-day

Vikings at its core. Though a number of communities across this

group of islands -- which lie over 300 miles from Edinburgh and

about as far north as St Petersburg, Helsinki or Anchorage --

celebrate Up-Helly-Aa, the event in Lerwick, the islands'

administrative capital, is the largest and most elaborate.

The celebration is overseen by the Guizer Jarl -- to all intents

the King for the day, a different one being chosen each year --

with help from his squad of fifty or so heavily armed Norsemen.

Up to a thousand costumed "guizers" (the word derived from the

disguises they wear) each carrying a flaming torch, help drag the

boat through the streets to its ceremonial burning. Until the

introduction of the torchlight parade in Edinburgh, this

procession through Lerwick was claimed as the biggest of its kind

in Britain, if not the world -- and still remains one of the

oldest.

Once the ship has been escorted to the burning site, the climax

of the pageant sees the torches thrown aboard and several months

of work quite literally goes up in smoke. With the burning over,

in true Viking style, the focus of the evening shifts to feasting

and revelry, with eleven halls around the town hosting

Up-Helly-Aa parties. The company of guizers, now divided into

squads, visit these halls in rotation where they perform to

entertain the assembled revellers, which may involve parodying

local events, topical satire or a more traditional offering of

music and dance. Local tradition holds that each guizer must have

at least one dance before being permitted his next dram. It is a

festival which continues until well into the next day, which,

understandably, is a holiday in Lerwick.

The Vikings arrived in Shetland a little over a

thousand years ago and although their presence is now long gone,

their influence remains on these islands, which at times still

seem more Scandinavian than typically Scottish. However, despite

this and the distinctly Dark Ages flavour of Up-Helly-Aa, the

festival probably owes its origins to rather more recent history. The Vikings arrived in Shetland a little over a

thousand years ago and although their presence is now long gone,

their influence remains on these islands, which at times still

seem more Scandinavian than typically Scottish. However, despite

this and the distinctly Dark Ages flavour of Up-Helly-Aa, the

festival probably owes its origins to rather more recent history.

While there does seem to be some evidence to suggest that rural

Shetlanders celebrated "Antonsmas" or "Up Helly Nacht"

twenty-four days after Christmas, there appears to be none which

points to a similar observance amongst the relatively urbanite

population of Lerwick. Festivities here seem to be only around

two-hundred years old, beginning after the end of the Napoleonic

Wars, with the return of soldiers and sailors complete with rowdy

habits and a liking of firearms.

At first, the revelry took place at Yule and New Year. A

Methodist clergyman visiting the islands described Lerwick's

Christmas eve of 1824 as "an uproar: from twelve of the clock

last night until late this night with blowing of horns, beating

of drums, firing of guns, shouting, bawling, fiddling, fifeing,

drinking and fighting. Thus was the state of the town all of the

night -- the street was as thronged with people as any fair I

ever saw in England."

The celebrations grew apace with Lerwick, until sometime in the

1840s, the rolling of burning tar barrels was introduced. As this

became more popular and the festivities ever more elaborate,

rival groups of tar-barrelers would often clash in the town's

narrow main street, this dirty and dangerous business leading to

many complaints from Lerwick's middle classes. Though the Town

Council attempted to control proceedings in response, it was not

until around 1870 that tar-barreling finally ceased.

At that time, changes implemented by a group of the town's young

men began the process of evolution for this post-Napoleonic riot

into the form of the modern festival. Borrowing from their rural

cousins' pagan history, they named it Up-Helly-Aa, moving it away

from Christmas towards the end of January, while introducing the

beginnings of costumed "guizing" and the torchlight procession,

both of which form central elements today. It seems that they

were also contemplating bringing a Viking theme to the new

festival but it was not until well into the 1880s that a longship

featured. The first Guizer Jarl made his appearance in 1906 and

it was not until shortly after the First World War that the squad

of Vikings became a regular part of the proceedings.

While Lerwick's festival cannot lay claim to the ancient pedigree

enjoyed by Burghhead or even, arguably, Stonehaven, it is

certainly one of the most spectacular fire-festivals anywhere in

the world, with a truly unique history all of its own and an

experience well worth having.

Locations and details:

Fireball Ceremony: Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire, 31st

December.

Stonehaven lies on the coast, beside the main A90

Dundee to Aberdeen road, just north of its junction with the A92

from Arbroath and about 12 miles south of Aberdeen city.

The organisers suggest being in the High Street around 11.15pm

(allow some extra time to park) to ensure a good view; they also

recommend wearing old clothes, for obvious reasons!

The Burning of the Clavie: Burghead, Moray, 11th

January.

Burghead is located on the Moray Firth between

Findhorn and Lossiemouth; access is by the B9013 off the main A96

Inverness to Aberdeen road, the turn off being approximately four

miles west of Elgin and eight miles east of Forres. Burghead is

also home to the remains of a fourth-century Roman Fort and may

even earlier have been the capital of the ancient Picts.

Up-Helly-Aa: Lerwick, Shetland Islands, last Tuesday in

January.

Shetland lies across 60oN -- approximately 100

miles off the north coast of Scotland. By air: From Edinburgh,

Glasgow, Inverness or Aberdeen - with connections available from

number of airports in Britain. Shetland's Sumburgh Airport is at

the island's southern tip, with buses hire cars and taxis

available for the trip to Lerwick, though pre-booking taxis and

cars is advised. By sea: NorthLink ferries operate regular

services from Aberdeen, while the Smyril Line sail from

destinations in Norway, Iceland, Denmark and Faroe.

The Flambeaux Procession: Comrie, Perthshire, 31st

December.

The small village of Comrie (not to be confused

with the one in Fife) is twenty miles west of Perth, on the A85

road to Loch Earn. As midnight chimes on the 31st December, a

small procession wends its way around the village before throwing

their fiery torches into the River Earn. It has been suggested

that this may have originated as a purification ritual. Nearby

attractions include the Deil's Cauldron waterfall and Lord

Melville's Monument.

The Biggar Bonfire:Biggar, South Lanarkshire, 31st

December.

Biggar lies on the A702, 10 miles north east of

junction 13 of the A74M and 25 miles south west of Edinburgh. For

many centuries the New Year has been ushered in with a huge

bonfire, lit by the oldest resident of the town, after a

torchlight procession.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Gareth Evans is a freelance writer and photographer, having previously worked in the private sector before lecturing at the University of Durham. Having travelled extensively, he now concentrates on writing about subjects much closer to home -- both geographically and metaphorically. He is particularly interested in myths, legends and folklore, together with the often forgotten history of the Celtic lands, especially that of his own native Wales and Scotland, his adopted home. Gareth is currently planning his next book, looking at the role of the pagan Horned God in myth and history.

Article and photos © 2005 Gareth Evans

Stonehaven Fireballs photo courtesy of the Stonehaven Fireballs website.

|